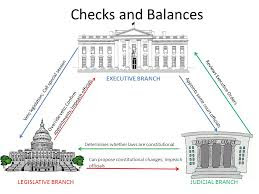

The Supreme Court has a special role to play in the United States system of government. The Constitution gives it the power to check, if necessary, the actions of the President and Congress.

It can tell a President that his actions are not allowed by the Constitution. It can tell Congress that a law it passed violated the U.S. Constitution and is, therefore, no longer a law. It can also tell the government of a state that one of its laws breaks a rule in the Constitution.

The Supreme Court is the final judge in all cases involving laws of Congress, and the highest law of all — the Constitution.

The Supreme Court, however, is far from all-powerful. Its power is limited by the other two branches of government. The President nominates justices to the court. The Senate must vote its approval of the nominations. The whole Congress also has great power over the lower courts in the federal system. District and appeals courts are created by acts of Congress. These courts may be abolished if Congress wishes it.

The Supreme Court is like a referee on a football field. The Congress, the President, the state police, and other government officials are the players. Some can pass laws, and others can enforce laws. But all exercise power within certain boundaries. These boundaries are set by the Constitution. As the "referee" in the U.S. system of government, it is the Supreme Court's job to say when government officials step out-of-bounds.

How the Justices Make Decisions

The decisions of the Supreme Court are made inside a white marble courthouse in Washington, D.C. Here the nine justices receive approximately 7,000 to 8,000 requests for hearings each year. Of these the Court will agree to hear fewer than 100. If the Court decides not to hear the case, the ruling of the lower court stands.

Those cases which they agree to hear are given a date for argument.

On the morning of that day, the lawyers and spectators enter a large courtroom. When an officer of the Court bangs his gavel, the people in the courtroom stand. The nine justices walk through a red curtain and stand beside nine tall, black-leather chairs. The Chief Justices takes the middle and tallest chair. "Oyez! Oyez! Oyez!" shouts the marshal of the Court. (It's an old Court expression meaning hear ye .) "God save the United States and this Honorable Court."

The justices take their seats. The lawyers step forward and explain their case. The justices listen from their high seats and often interrupt to ask the lawyers questions. Several cases may be argued in one day. Finally, in the late afternoon, the Chief Justice bangs his gavel, rises from his seat, and leads the other justices through the red curtain out of the courtroom.

The justices may take several days to study a case. Then they meet around a large table in a locked and guarded room. From their table, they may occasionally look up to see a painting on the wall.

It is a portrait of a man dressed in an old-fashioned, high-collared coat. This man is John Marshall, one of the greatest Chief Justices in American history. More than anyone else, he helped the Supreme Court develop its power and importance.

Before Marshall became Chief Justice, the Supreme Court had not yet challenged an act of Congress. The Constitution did not clearly give the Court power to judge laws passed by Congress. Therefore, the Court wasn't even sure it had this power.

But Marshall made a daring move. In a famous court case in 1803, Marbury v. Madison, he wrote the Court's opinion, which declared a law passed by Congress to be unconstitutional.

This decision gave the Supreme Court its power of judicial review. Ever since, the highest court has used the power to review the nation's laws and judge whether they were allowed under the Constitution. It has also reviewed the actions of the President.

The Constitution does not allow Congress or state legislatures to pass laws that "abridge the freedom of speech." Freedom of speech is protected in the United States, and no lawmaking body may interfere with that freedom. Right? Usually. But there may be limits, even to free speech.

No freedom, even one specifically mentioned in the Constitution, is absolute. People convicted of serious crimes lose their right to vote. Some religions encourage a man to have several wives. But that practice is forbidden in the United States, even though the Constitution says that there shall be no laws that prohibit the "free exercise" of religion. Even words themselves may pose a "clear and present danger" to the well-being of the country.

When are mere words so dangerous that Congress (or a state legislature) may limit the freedom of speech?

That is the sort of difficult question that the Supreme Court justices must often answer.

Here's an example. The justices sat around the conference table in their locked room, trying to decide what to do about a man from Chicago named Terminiello. The year was 1949.

It seems that Mr. Terminiello had given a speech to an audience in a hall in Chicago, attacking all sorts of people. A crowd had collected outside the hall to protest. Terminiello had called the crowd "a surging, howling mob." At other points in his speech, he called those who disagreed with him "slimy scum," "snakes," "bedbugs," and the like. The crowd outside screamed back: "Fascists! Hitlers!" Windows were broken, a few people were injured, and Terminiello was arrested. For what? All he did was talk. But by talking, he broke the law.

This Chicago law outlawed speech that "stirs the public to anger, invites dispute, (or) brings about a condition of unrest." But maybe this law was unconstitutional.

Justice William Douglas said that the Chicago law went against the First Amendment. He said that freedom of speech is important because it invites dispute. It allows people to raise tough questions, questions which should be answered in a democracy. Just because people get angry or annoyed at something that is said, Justice Douglas went on, does not mean that it should not be said.

Justice Robert Jackson felt differently. Yes, he agreed, Terminiello had not said anything illegal. But because of the crowd and the anger around him, his speech was dangerous to the peace and order of the community. Therefore it was not protected by the First Amendment. There is a point, said Justice Jackson, beyond which a person may not provoke a crowd.

Finally the Court voted. Each justice, including the Chief Justice, had one vote. Five agreed with one opinion, four with the other. One of the justices in the majority was then asked to write a long essay explaining the legal reasons for the majority's decision. Another justice announced that he would write a dissenting opinion. This was an essay telling why he disagreed with the Court's decision.

How do you think the Court ruled in Terminiello v. Chicago?

What if Terminiello had been a Republican campaigning for office among bad-tempered Democrats? What if he had been a Communist? Consider these and other important questions that might occur to you. Which is more important: protecting free speech, or the peace and order of the community? Where do you draw the line?

If you had been on the Court in 1949, would you have voted to allow the Chicago law to stand, or would you have voted to rule it unconstitutional?

credit:

http://www.socialstudiesforkids.com/articles/ushistory/brownvboard.htm#sthash.0APx7AJB.dpuf